Rising from the red tinted alluvial soil of Sylhet, Northeast Bangladesh, Srihatta is the future home of the Samdani Art Foundation, rooted in the plurality found in Bangladesh’s history to conjure a more inclusive future through art, architecture, and culture. A unique combination of sculpture park, exhibition, residency, and education programme, Srihatta imagines what an experimental artist-centric institution can be in the 21st Century, beyond of western-centric paradigms. Founded by Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani and led by Artistic Director Diana Campbell Betancourt, this art centre and sculpture park will also feature works from their collection and will be free and open to the public in 2021.

About Sylhet

Srihatta – the Samdani Art Centre and Sculpture park is located in Sylhet, Bangladesh, a lush and green rural tea district approximately 250km (or a 45 minute flight) from the capital city of Dhaka, and Sylhet International Airport has direct flights from London, Dubai, and Abu Dhabi. There are nearly 800,000 people living in Sylhet, and Sylhetis form a significant part of the Bangladeshi diaspora in the United Kingdom, United States, and Middle East. Founders Nadia and Rajeeb Samdani are both from Sylhet and Srihatta is part of their long-term dream to share their love of art and this region with artists and the public.

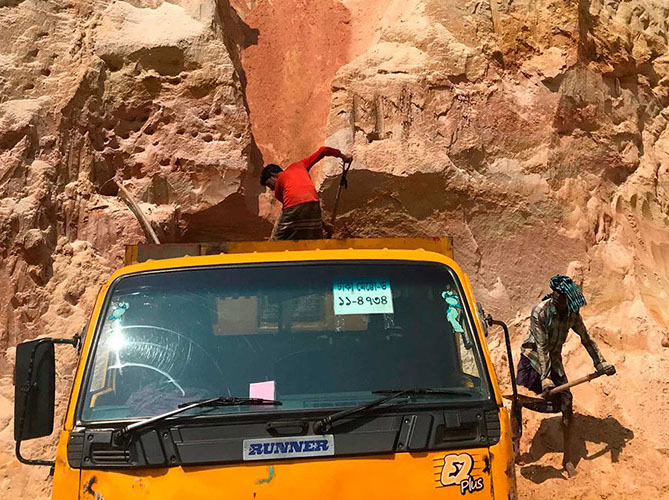

The roughly 40-minute drive to Srihatta from the airport is a journey through the agriculture landscapes of Sylhet through villages built around winding rivers and tea plantations built on hilly mounds punctuating an otherwise flat landscape. The many paddy fields make the landscape appear like a massive waterbody during the rainy season. Srihatta’s landscaping will be inspired by the wild natural wonders of the lands around the site which include gnarled mangrove swamp forests, turquoise rivers, and multicoloured sand hills and the art gallery will appear to float within a lush grassy paddy field.

Reflecting the energy and vibrancy of the Bangladeshi people, Srihatta will be a live, active, changing and dynamic space with an emphasis on process, which differs from traditional ideas of sculpture parks and artists will be at the centre of this project via Srihatta’s international residency programme. Srihatta spans across more than one hundred acres of landscape with views of India’s Assam Hills in the distance.

About the name Srihatta

The interwoven Animist, Hindu, Buddhist, Sufi mystic, and Islamic histories that inform Sylhet’s plurality and distinct language remain powerfully visible in Bengali folk culture. Srihatta’s name is an homage to the multiple layers of history that have shaped this rich landscape; it is the ancient Indo-Aryan term for Sylhet. In this area once there was abundance of rocks know as shila. The hat (bazaar) sat on top of these rocks. The name of Sylhet was derived from the words ‘Shila’ and ‘Hat’ as Shila-Hat - to form Shilhatta. The last Hindu King Raja Gour Govinda kept large stones for protection at the entrance of his capital Shilhatta, whose name was transformed over time into Srihatta – with sri meaning, beauty, charm and wealth. The early 14th century brought the beginnings of Islamic culture and rule to Sylhet via the Middle Eastern Sufi mystic Hazrat Shahjalal and his 313 companions. On his arrival to the capital, Hazrat Shahjalal commanded the rocks to move away by uttering the term ‘Shill Hot’ (move away, stones), and local legend has it that the rocks moved to usher in a new era and the name Silhet came into existence. During the British colonial rule over the region, the word Sylhet was introduced to make ‘Silhet’ sound distinct from ‘Silchar’ (a town in Assam). Sylhet was a strategic location for the British during the colonial era because of its proximity to Burma and China.

Architecture

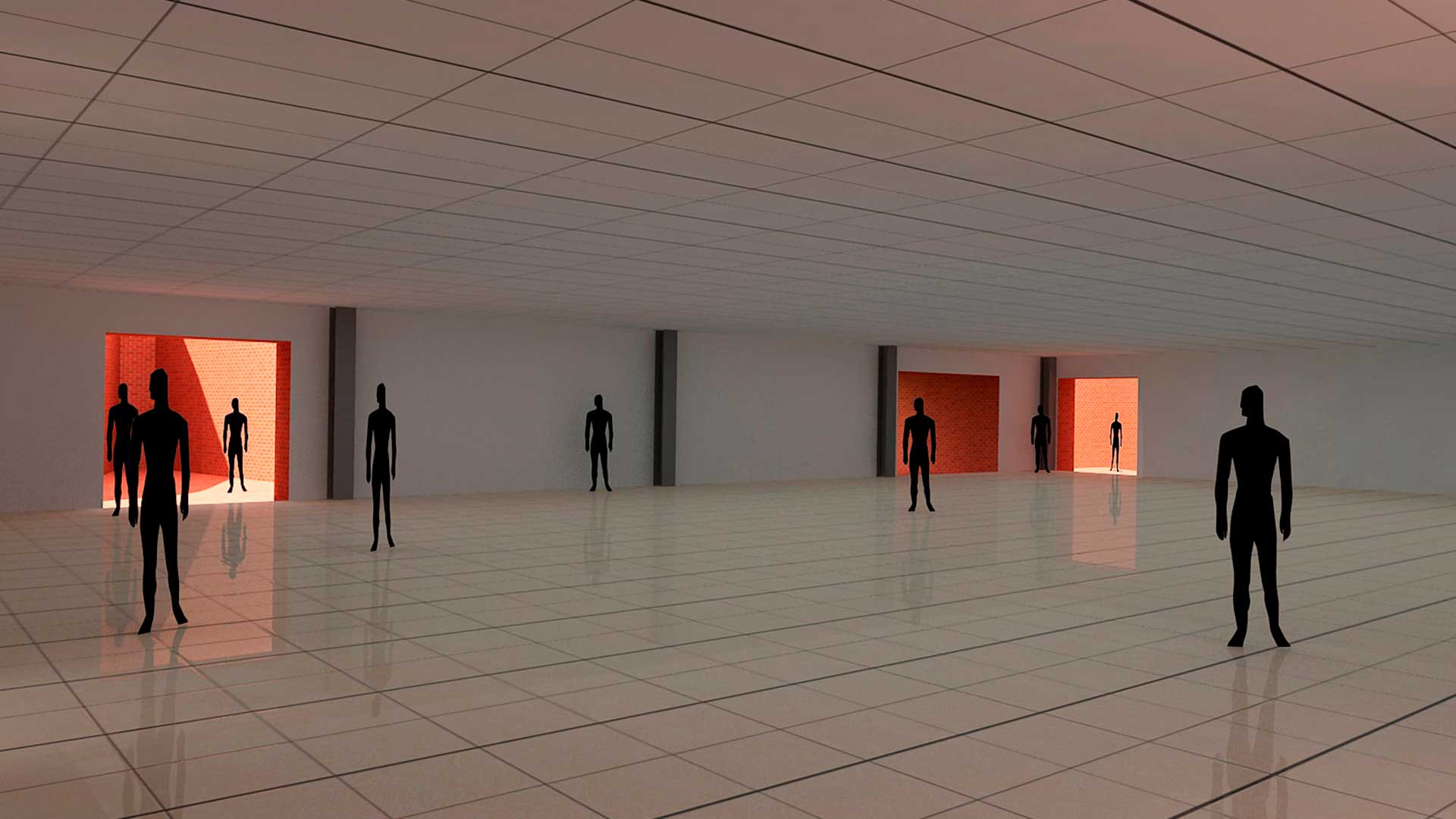

Aga Khan Award winning Bangladeshi architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury (URBANA) has envisioned the initial phase of Srihatta as an open plan design that references the vernacular brick architecture of Bangladesh, a practice dating back to 3rd Century BC. The architecture looks to the modernist legacy left by visionary architects such as Muzharul Islam and Louis Kahn, who built some of their best work in Bangladesh, including the Dhaka University Library (1953-1954) and Jatiya Sangsad Bhaban (Parliament House, 1961-1982). Aligned with the ideology of the Samdani Art Foundation, Chowdhury’s architecture is born from the land of Sylhet: the brick-dyed concrete found in Srihatta’s built environment is derived from the colour of the soil on site.

A 10,000-square-foot residency space will house eleven brick-dyed, cast-concrete apartments, with windows facing Srihatta’s landscape. Created as a meditative space to inspire creativity and mesmerize the senses, these apartments will have 11-foot ceilings – each with a different species of local scented tree to grow inside.

The apartments, dining, recreation, and reading spaces are visually linked by an additional 10,000 square feet of plazas and walkways made of local green-tinged grey Kota stone. Blending the residency space with the surrounding landscape and sculpture park, the complex will exhibit works from the Foundation’s collection on a rotating basis.

In addition to residencies with local and international artists, Srihatta will also host future writing and curatorial residencies as part of a wider initiative of training a new generation of arts professionals in Bangladesh. The Residency program will be organized by SAF, with additional collaborations with international foundations and cultural councils, and independent from the Samdani’s collecting activities.

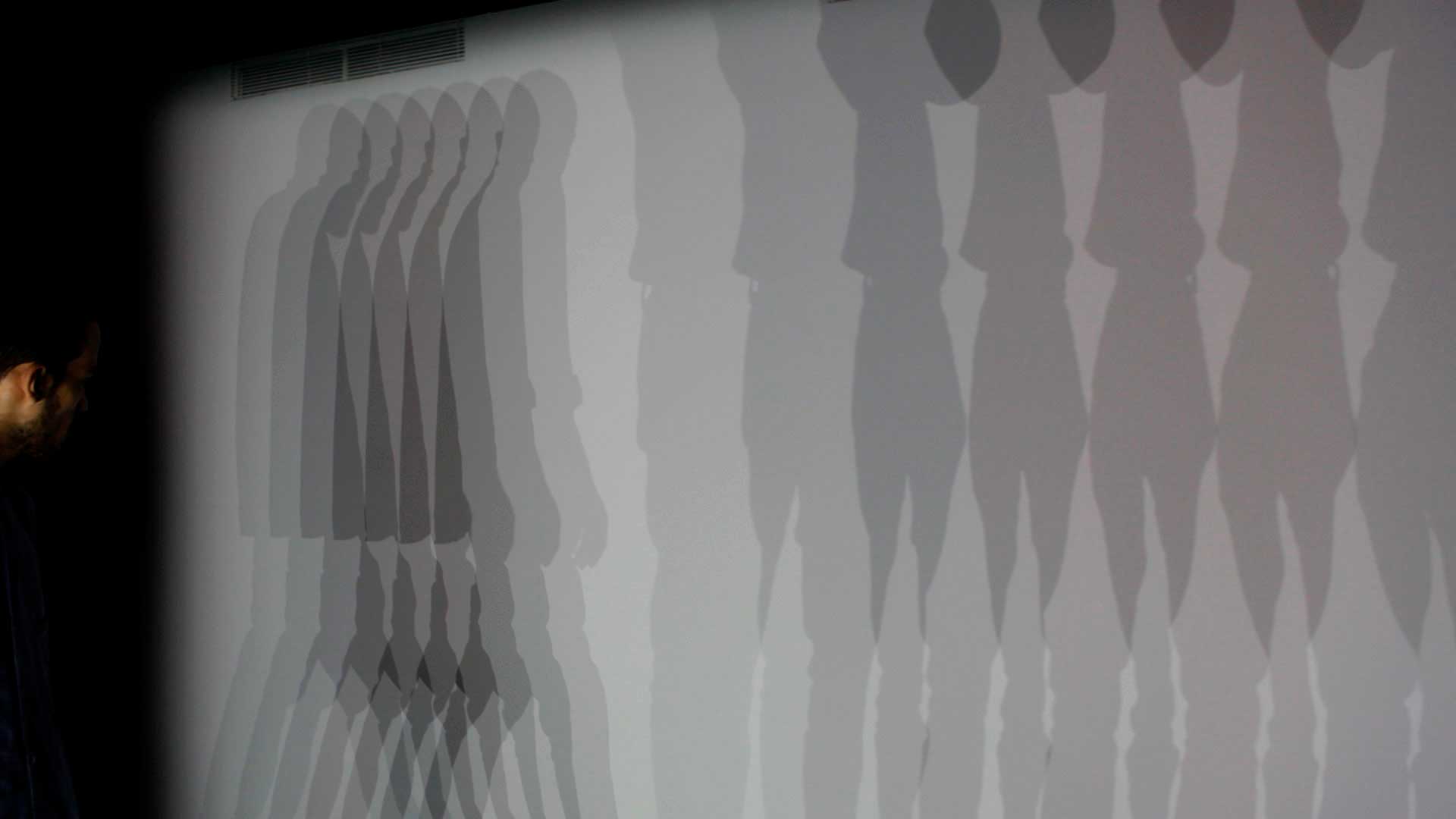

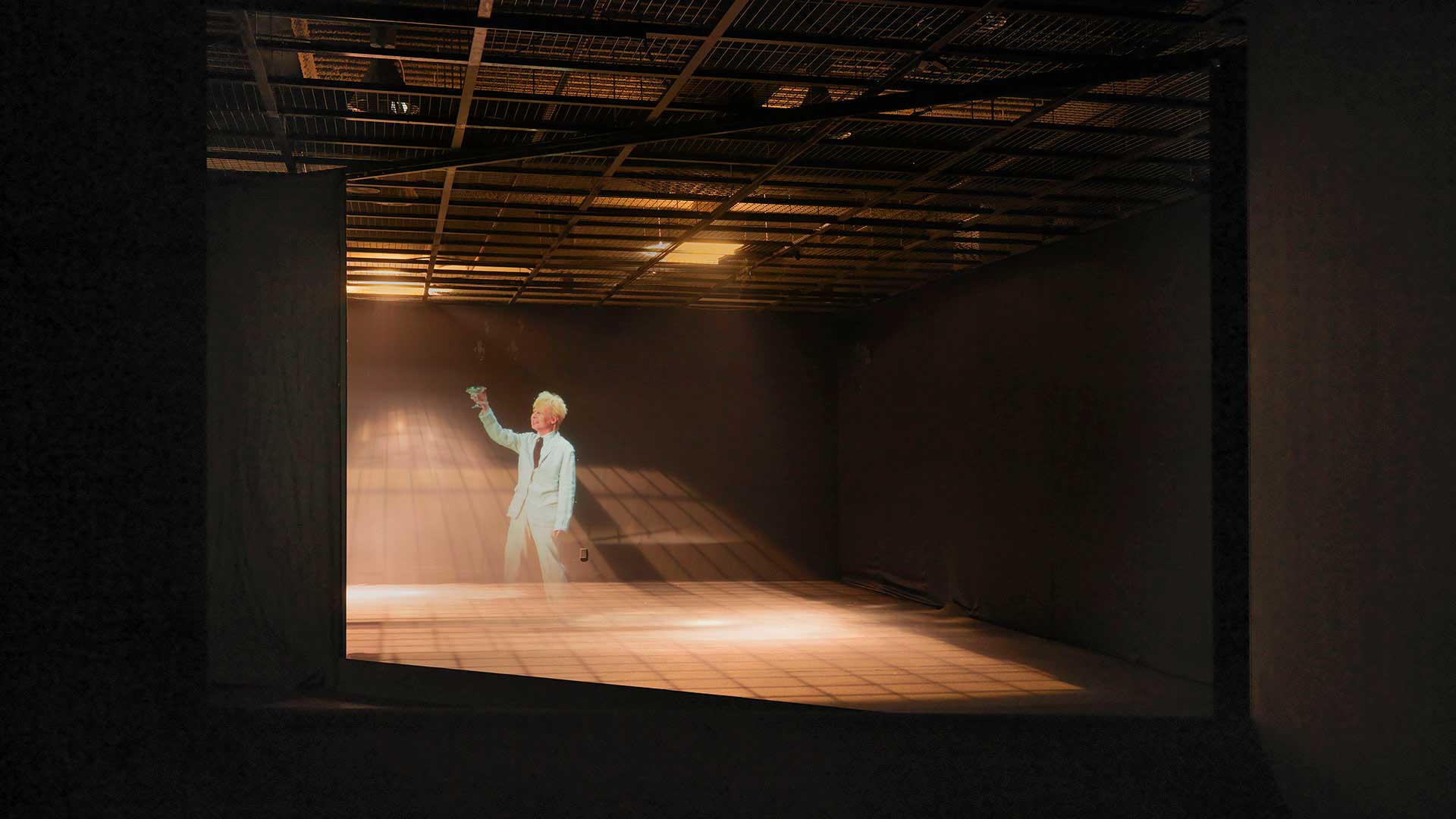

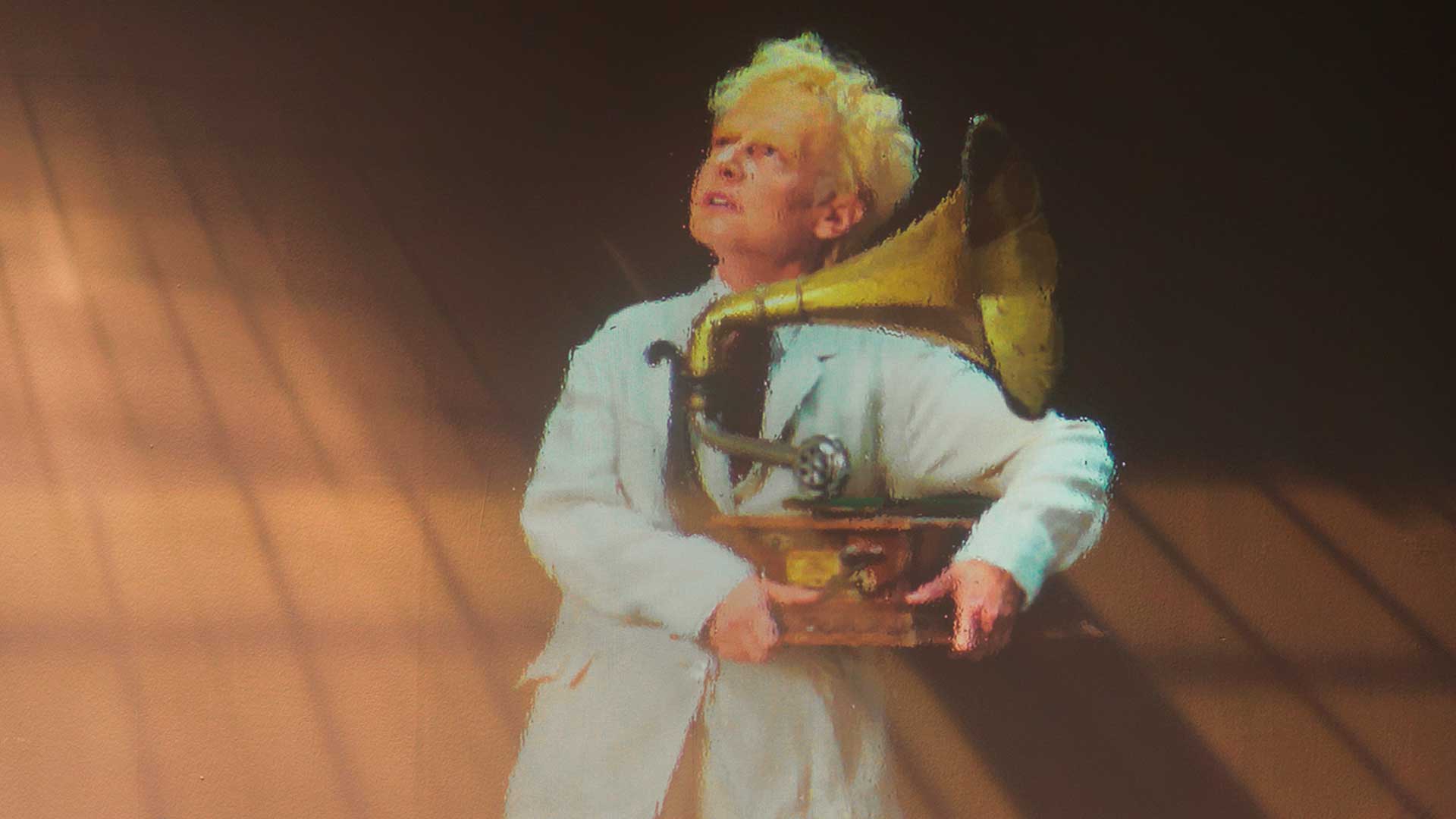

Chowdhury has also designed the first of several future gallery spaces at Srihatta. An undulating brick façade welcomes visitors into a 5,000 square-foot gallery with 14-foot ceilings anchored by an immersive installation of video, sound, and expanded cinema works from the Samdani collection by Cardiff and Miller, Olafur Eliasson, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Anthony McCall, and Lucy Raven which challenge boundaries between mediums.

Future galleries will be built to allow for rotating temporary exhibitions produced by the Samdani Art Foundation.

Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury

Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury graduated in architecture from the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) in 1995. After working with architect Uttam Kumar Saha, Chowdhury established the practice URBANA as a partnership in 1995, and from 2004, continued as the Principal of the firm. Chowdhury has been a visiting faculty member at the North South University and BRAC University, both in Bangladesh, and has been a juror of final year critiques for universities in Dhaka. Chowdhury was twice a finalist in the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, and won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2016 for the Friendship Centre. He was the first Bangladeshi architect to feature in the central curated exhibition in the Venice Biennale during the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, ‘Reporting from the Front’. He won first prize in the 2016 International Baku Architectural Ward and was a finalist for the 2016 BSI Architectural Award in Switzerland. In 2012, Chowdhury was awarded Architectural Review’s AR+D Emerging Architecture Award.

Kashef Chowdhury has a studio-based practice, creating work that finds its root in history, with strong emphasis on climate, materials and context – both natural and human. Projects in the studio are given extended time for research so as to realise a level of innovation and original expression. Works range from the conversion of ships and low-cost raised settlements in ‘chars’ to training centres, mosques, art galleries, museums, residences and multi-family housing to corporate headquarters.

Artistic Programme

Envisioned as a dynamic art centre, Srihatta embraces inclusivity with a welcoming design, an accessible public programme, and outdoor public works which engage the local community in their conception and production. More than just a private art museum, Srihatta aspires to cultivate a new community of art lovers in Bangladesh and the surrounding region. As with all Samdani Art Foundation activities, entry to Srihatta will be free, in an attempt to make art widely accessible to diverse audiences. Srihatta’s programming complements – but remains autonomous from the Dhaka Art Summit (www.dhakaartsummit.org).

Led by Samdani Art Foundation’s Founding Artistic Director Diana Campbell Betancourt, Srihatta encourages engagement with Bangladesh’s rural context. The organization will invest its roots locally – and broaden them internationally – by inviting artists, curators, architects, and writers from around the world to participate in its exhibitions, residencies, interventions in the landscape, and to engage in creative workshops with the local community. Srihatta is inspired by the ethos of Rabindranath Tagore, who created Shantiniketan in a village in West Bengal in 1901 – where the whole world could meet in a single nest.

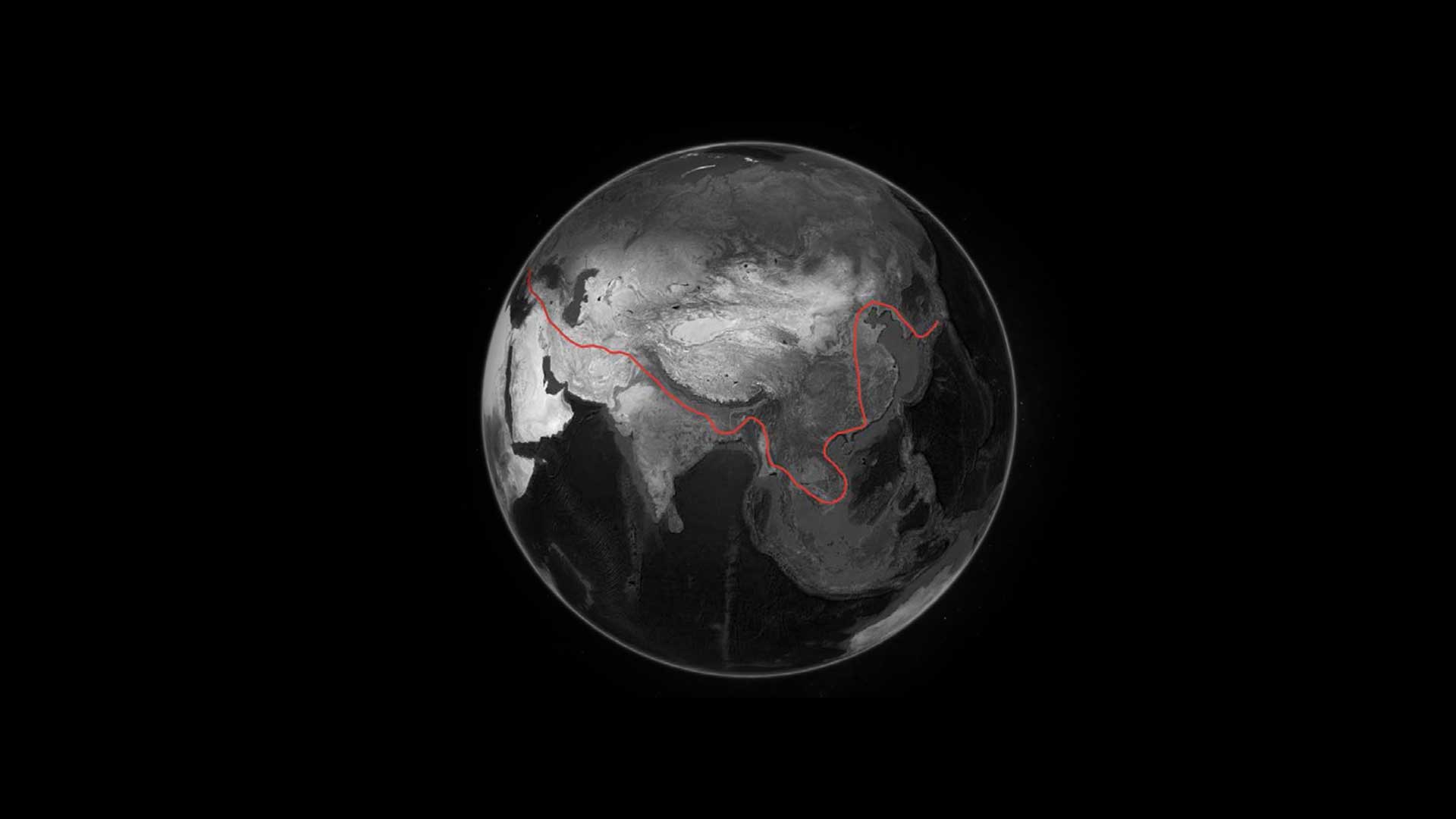

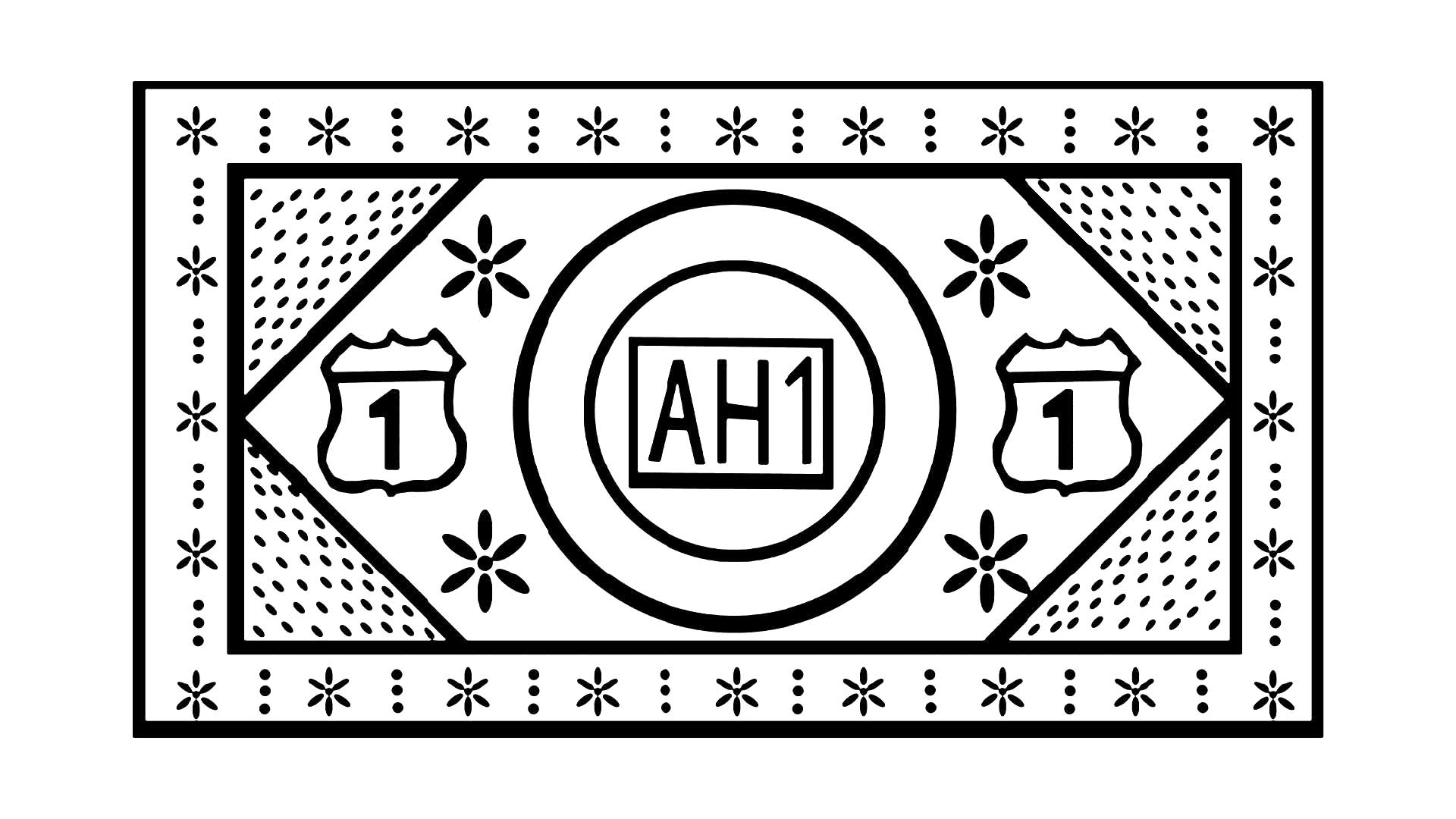

A conceptual anchor for the space is Superflex’s AH1 – a project inspired by an abandoned modernist dream of building a highway connecting Tokyo to Istanbul which if realized, would have gone through Sylhet and nearly through Srihatta. Srihatta will be a place to imagine new points of solidarity outside of colonial frameworks and build upon utopian dreams from the past to chart a better and more inclusive and tolerant future.

Sculpture Park

The first phase of architectural elements of Srihatta will take up only a half-acre of the 100-acre property, with the majority of the grounds comprising a sculpture park. URBANA’s plan for the landscape design will embrace the natural phenomena that surround the site: winding rivers, a swamp forest, golden hills made of sand, and flaming natural-gas-fields with views of India’s Assam Hills and Sylhet’s tea gardens in the distance. Site-sensitive commissions by artists from Bangladesh and around the world will further transform the landscape.

Over the past three years, Srihatta has been welcoming artists to develop long-term projects for the site, asking that each engage with the site and surrounding community. Once open, Srihatta will include a mix of permanent works, temporary works, and works on long-term loan, in an attempt to make Srihatta a living, evolving entity that changes regularly and welcomes repeat visits. All of the works in the sculpture park will be produced in Bangladesh, as part of the Foundation’s desire to engage the local community with craftsmanship and production, fostering collaboration as a tool for greater understanding.

While Srihatta officially opens in 2019, the first work for the Park, ‘Rokeya’, was completed in February 2017 after two years of development – and speaks to the socially engaged practices that the institution plans to regularly host. As part of the annual Samdani Seminars programme, Polish artist Paweł Althamer – along with members of his community (neighbours) from Bródno, Poland – engaged patients of Protisruti (the Promise) drug rehabilitation centre in Sylhet and the local community in an eight-day-long creative and collaborative Sculptural Congress workshop. This first project at Srihatta was realized in partnership with Bródno Sculpture Park, which Pawel Althamer inaugurated in 2009 with the Museum of Modern Art Warsaw. Bridging understanding across social and cultural divides, they created the communal work of art, ‘Rokeya’, which the village children named after the nineteenth century pioneer of female education in Bangladesh, Begum Rokeya. The resulting sculpture is a reclining woman constructed of locally woven palm fronds over a bamboo frame. She wears a colourful fabric costume stitched from local textiles by nearby village women, who also helped to drape the fabric. ‘Rokeya’ also contains a kiln inside, for village children to use in ceramic workshops.

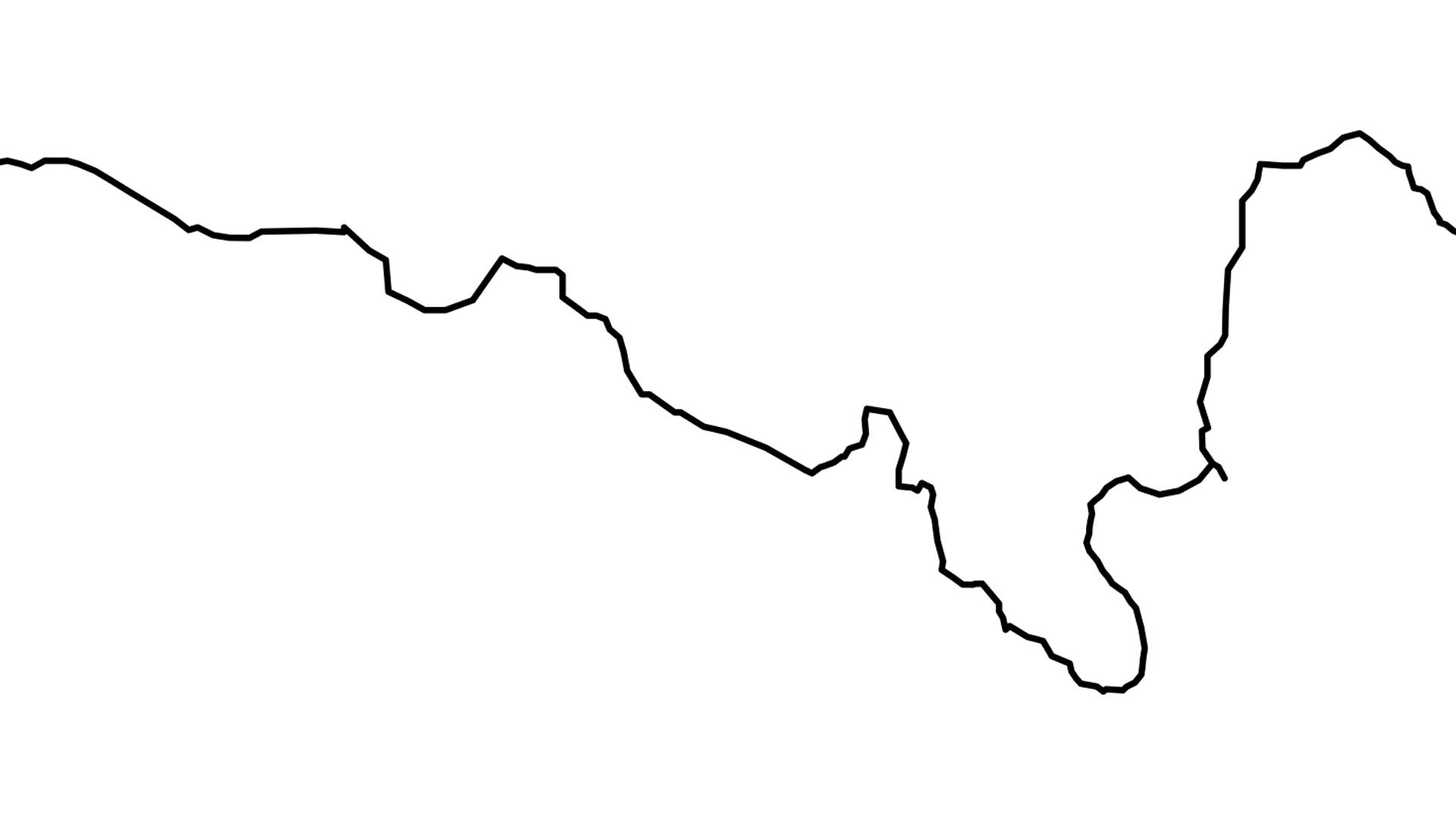

Srihatta continues its initial collaboration with Bródno Sculpture Park into 2019 with Polish artist Monika Sosnowska who will realize a monumental concrete river that becomes a walking path through the landscape. Here tributaries will meander through and disappear into unexpected places, allowing for contemplation of one’s surroundings. The piece ties back to the natural terrain of Bangladesh, which has over 700 rivers (and is officially the country with the most rivers within its borders).

Indian artist Asim Waqif has begun the initial planting of bamboo saplings for what will become a monumental living sculpture titled ‘Bamsera Bamsi’ (meaning Bamboo flute in Bangla). The sculpture is envisioned as a living bamboo forest, consisting of several bamboo species researched and planted as part of a long-term collaboration with the Bangladesh Forest Research Institute, Chittagong. As it grows, Waqif will sculpt the forest into a sculptural wind instrument reminiscent of a flute, which will emit sound when the wind blows through it. ‘Bamsera Bamsi’ will take nearly two years before it will be audible, and five years to be fully mature. The initial size of the work is 140 x 100 ft and will expand as the project develops.

Emerging Nepali artist Subas Tamang, the descendent of a family of indigenous stone carvers, has expanded upon his series ‘I Want to Die in My Own House’ in his commission for Srihatta, creating monumental slate roofs inspired by a fading form of vernacular South Asian architecture that was once prevalent across South Asia. Intricately carved with the images of Tamang’s migrant worker parents and migrant workers that the artist met during his residency at Srihatta, this work seeks to articulate the dreams of many people: to own their own homes and to live life on their own terms.

In collaboration with the children from Srihatta’s nearest local village, the renowned French architect Yona Friedman will realize an aerial drawing inspired by the mythology of Ancient Bengal, to be shaped from local stones sourced in Sylhet. This drawing will be visible both from the hilltop site of the Artist Residency space, but also from planes and helicopters flying over Sylhet.

Sylheti born artist Rana Begum has created a sculptural teahouse celebrating light and color in the landscape. The perforated walls of the teahouse, made of locally available industrial materials, are painted in a myriad of colors that transform as visitors open and close various panels and as the sunlight moves across the panels. This sensory space is a place to host conversations among visitors and artists.

A conceptual anchor of the space is Superflex’s commission ‘AH1’ (Asian Highway 1), a large-scale sculpture depicting a fragment of the utopian AH1 otherwise known as The Asian Highway 1. This was a 21,000km modernist dream that proposed connecting Istanbul and Tokyo, which was never realised. Should it have been realised the highway would have nearly passed though Srihatta on its path through Sylhet. The art work will be made of the most traditional material in the region: bricks. The art work will also function as a pavilion and view point for the visitors of the park and a place to contemplate building new solidarities outside of western colonial paradigms.

A rite of passage can be described as a ceremony marking when an individual or individuatls leave one group/society to enter another, a harbinger of impending change. Moving towards the de-hegemonisation and decolonisation of form, Rasheed Araeen’s monumental commission ‘Rite/Right’ of Passage (2016-2018) serves as a transitional space to enter the area around the Srihatta residency space and to consider a space where art can be produced and thought about without relying on or perpetuating western-centric discourse.

Additional artists with commissions to be completed by Srihatta’s opening include Raphael Hefti, Susan Philipsz, Raqs Media Collective, Mithu Sen, and Ayesha Sultana.

Responding to Sylhet as a site of pilgrimage and to the human sounds vibrating over its landscape, Haroon Mirza is developing an ambitious commission of a cylinder-shaped brick pavilion with an installation on the roof made of solar panels that are arranged in patterns inspired by sacred geometry. Each day during the five calls to prayer, a sound and light installation composed by Mirza will interact with the spiritual sounds outside, connecting and shifting our state of perception into a higher state of consciousness.